Income Return vs Total Return

I suppose that the natural way of viewing investment returns by the average investor is to try and figure out what income yield such investment is effectively leaving him in his pocket – that is hard, cold cash. As an investment advisor myself, countless are the occasions I come across clients or prospective clients who, albeit not necessarily in need of income, would still have a bias towards income-yielding investments. I usually argue back that income return is only one factor in the equation through which return, or potential return, is generated. A desirable return objective could likewise be generated from favourable price movements through time.

By simply focusing or picking up those investments distributing the highest income return, one would be automatically constrained to a limited pool of asset classes or sectors from which to choose. In today’s low-yielding environment, chasing highest yields when building up an investment portfolio has become complicated and riskier than ever before. We are no longer living in the 80s, whereby an investor could easily lock-in a double-digit income yield by simply holding a 1-year term deposit at the bank.

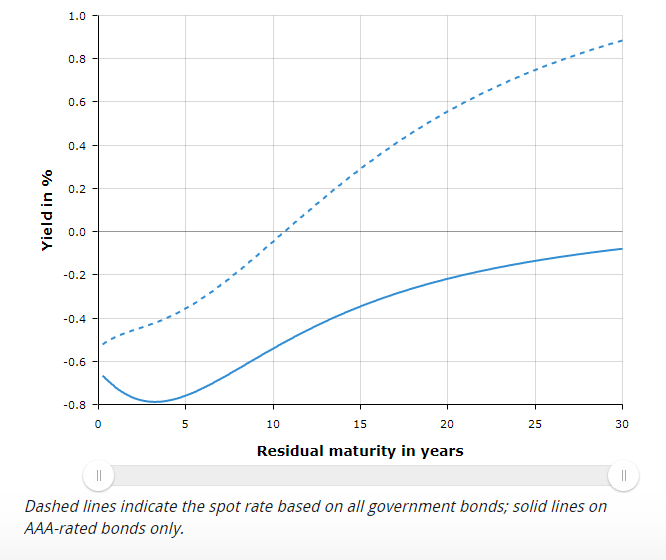

From a psychological point of view, and from experience, investors seeking an income return are usually satisfied if they manage to lock-in an income yield of 4 to 5%. In today’s day and age, if we had to look at the broader European bond market, government bond yields are yielding a negative return up to 10 years of maturity. To add insult to injury, AAA government bonds, or the German-Bunds, yield a negative return up to the 30-year mark in the yield curve spectrum.

Source: ECB

However, the question one should ask before opting for an investment is: should I solely focus on the highest yielding assets? Should I choose investment A, as opposed to investment B, simply because the former has more of an attractive headline distribution yield? In the next few lines, I will try and explain my rationale as to why the answers to such questions should be ‘no’.

Yes, it is true that some investors’ objective purely revolves around income return, because they are dependent on it. Be it to top-up current pension income, maintaining a decent standard of living, or to meet regular expense commitments which require a certain level of regular income stream from the investment portfolio.

What one needs to extremely be careful about however, is not to overlook the level of risk being undertaken in order to chase that extra 1 to 2% in income return. Even when it comes to investing in collective investment schemes, due consideration needs to be made as to why the distribution yield varies across different schemes. Is it purely related to the asset classes in which the scheme is investing in? For example, a strategy focusing on emerging market bonds as a sub-asset class within the fixed-income universe will typically offer a higher distribution yield than a strategy focusing on high-yielding corporate bonds, which in turn will be higher than an otherwise investment-grade corporate bond strategy, or a portfolio made up of government bonds issued by developed countries.

Apart from the sub-asset class itself, another factor that should be given due consideration is the charging structure of the scheme and duration. As an example, suppose two different schemes have a similar investment mandate – to invest in high-yielding corporate bonds. One scheme offers a 100-150 basis points difference in the yield distributed compared to the other. Ceteris paribus, one could understandably opt for the highest-distributing strategy because of the individual’s dependency on income. However, one thing I have learnt back in my economics classes is that: “there is no such thing as a free lunch” [1]. The investor should try to at least understand why the higher yield. Reasons for this could be various: either the average duration chosen by the fund manager is on the high side compared to the other; the average credit quality is at the lower end of the risk spectrum, example more weighting into CC-rated bonds as opposed to BB-rated bonds; or perhaps the geographical allocation itself – for instance US Treasury bonds have been offering a spread over the German bunds for numerous years. In such cases, one should then also assess the currency risk being exposed to for that spread.

Even if we had to assume two same exact strategies with comparable underlying investments. It could still be the case that one fund distributes a higher income yield simply because the annual management charge (AMC) of the fund is deducted from capital rather than from income. Despite implying a higher distribution yield, the cost to it is less capital protection.

One other example with which I would like to conclude with in order to portray the importance of not just focusing on the headline distribution figure, is by comparing the local government bond market to the local corporate bond market. If we had to go back to January 1, 2019, and observe what yield could be achieved from the two distinct fixed-income sub-asset classes, an income-focused investor would easily opt to invest in the corporate debt front – offering a much more attractive income return, hovering around 3.5% to 5%. Making reference to the MSE Corporate Bond Total Return Index and the MSE Malta Government Stocks Total Return Index, with hindsight, one might regret the decision to have ignored one sub-asset class over the other simply by basing his decision on the income yield. Since the beginning of the year, the MSE Corporate Bonds Total Return Index registered an overall advancement of 1.51%; whereas the MSE Malta Government Stocks Total Return Index appreciated by 12.69%[2].

I am not trying to suggest that government bonds are better than corporate bonds because the two sub-asset classes are totally distinct in terms of duration and credit risk. Moreover, the government debt market needs to be taken in the context of the dovish tone adopted by the European Central Bank throughout this period, which exacerbated the upward trend in government bond prices. However, in constructing an investment portfolio, I do suggest consideration of other asset classes or sub-asset classes within a portfolio which will definitely play a bigger role in achieving a more optimal risk-adjusted return over the medium-to-long term. For instance allocating equity within an investment portfolio could be strategically important, particularly if mitigating inflation risk is one of the goals trying to be achieved.

[1] In the context applied by economist Milton Friedman

[2] Source: MSE, as at September 26, 2019

Colin Vella, CFA is Head of Wealth Management at Jesmond Mizzi Financial Advisors Limited. This article does not intend to give investment advice and the contents therein should not be construed as such. The Company is licensed to conduct investment services by the MFSA and is a Member of the Malta Stock Exchange and a member of the Atlas Group. The directors or related parties, including the company, and their clients are likely to have an interest in securities mentioned in this article. Investors should remember that past performance is no guide to future performance and that the value of investments may go down as well as up. For further information contact Jesmond Mizzi Financial Advisors Limited of 67, Level 3, South Street, Valletta, on Tel: 2122 4410, or email [email protected]